Plumeria in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine

The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew is a place that I dream of visiting someday. Located along the River Thames in southwest London, it is known for being the largest and most diverse collection of plants and fungi in the world. The gardens span 132 hectares (330 acres) and there are numerous conservatories and ornamental buildings. It is also one of the top three largest herbariums in the world, holding ~7 million dried plant specimens and is a World Heritage Site. Though the Kew site formally dates back to 1759, it was founded in 1840 as a national botanic garden.

Many botanical gardens, like Kew, have colonial origins, and focused on finding and growing ornamental garden plants. William Curtis (1746–1799) was one of the early botanists at Kew who published illustrated gardening and botanical works. Curtis started out as an apothecary, an ancestral version of our modern day pharmacist, but his interests led him to natural history as an entomologist, studying insects, and as a botanist. He wrote Flora Londinensis, a six volume scientific work that described the flora of London. All of the descriptions included hand-colored copperplate illustrations. Many written works during this time not only aimed to reach the scientific elite but also aimed to reach amateur naturalists. One of Curtis’ early works, Instructions for collecting and preserving insects; particularly moths and butterflies, was a practical guideline which he self-printed when he was only 25.

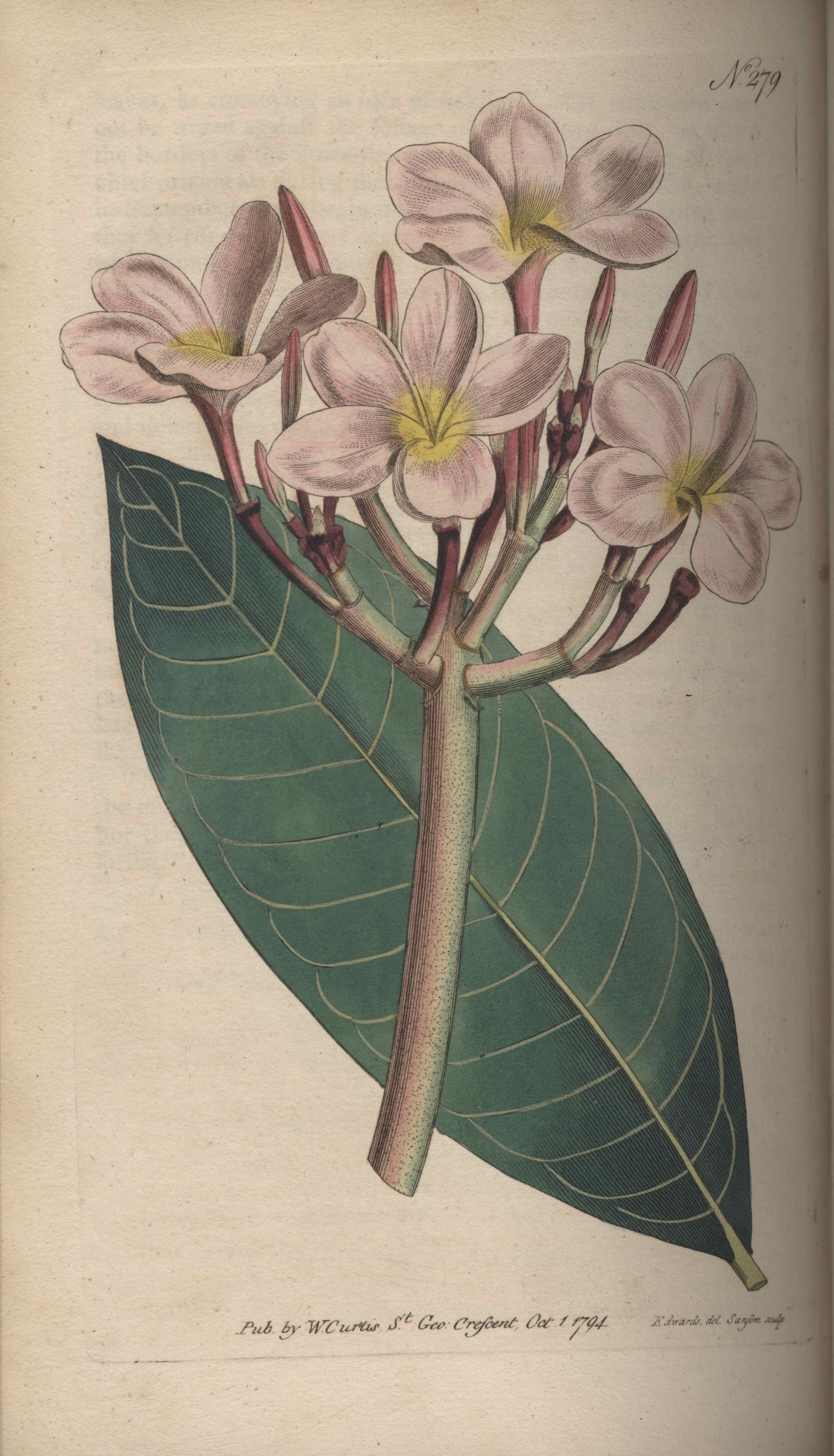

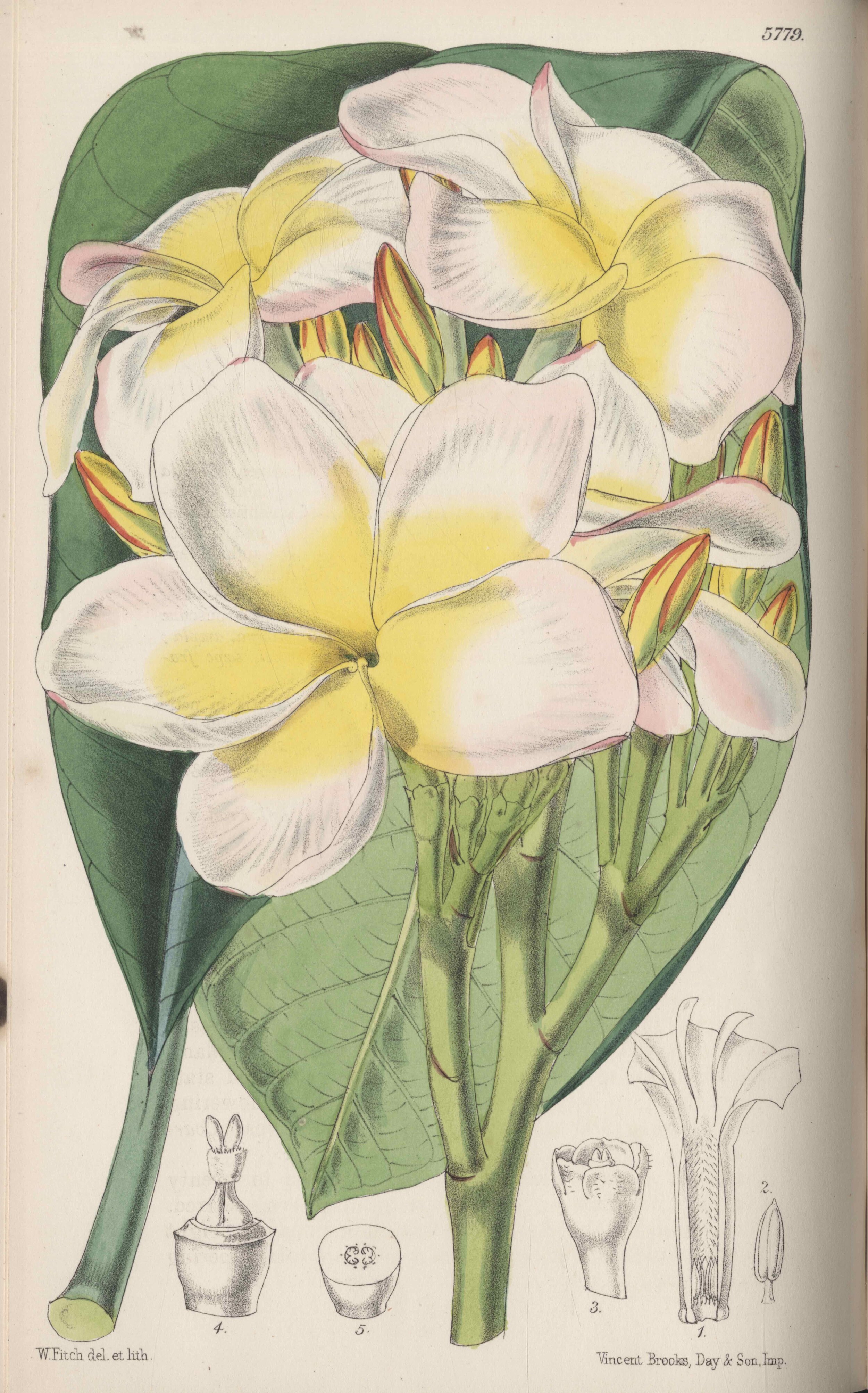

Curtis is best known for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, an illustrated periodical that began in 1787 and is still published today. Plants were described in formal but attainable language, some for the first time, and published along with a detailed watercolor illustration. Curtis published 13 volumes before his death, and other prestigious botanists like Joseph Dalton Hooker who became the Director of Kew Gardens in 1865 took up editorial responsibility. The Magazine continues to be published by Kew Gardens and is the oldest and most widely cited work of its kind. It appeals to the interests of horticulture, ecology, economic botany, history, and botanical illustration. The illustrations are life-sized and demand extreme attention to detail and require that the artist work closely with the botanist for accuracy. The artists are equally as important as the botanists for this publication. The entire collection of illustrations is part of the permanent collection at Kew.

Plumeria first appeared in the Magazine in 1794 by Curtis and appeared three more times in the 19th century. All four taxa are currently considered synonyms of Plumeria rubra, the most commonly cultivated species. The first Caribbean endemic species of Plumeria to be featured in the Magazine is Plumeria filifolia, a thin-leaved species from Cuba. The publication came out in March and features an overview of the genus in the Caribbean, a historical overview of the early collections of P. filifolia, distribution maps, and photographs from the field. Along with a magnificent watercolor, there are detailed illustrations done by Cuban artist Julio Figueroa who now lives in Miami. Before immigrating to the US he was the scientific illustrator for the Faculty of Biology at the University of Havana and Cuba’s National Botanic Garden. This work is part of my dissertation research and could not have been done without the collaboration of Dr. Ramona Oviedo, a distinguished botanist and curator at the National Herbarium of Cuba (HAC). She also holds an honorary appointment at the Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática in Havana, Cuba.

You can read the Plumeria filifolia article here.

Photos:

Plumeria rubra t. 279 (Curtis, 1794),

Plumieria acuminata W.T. Aiton t. 3952 (Hooker, 1842),

Plumieria Jamesoni Hook. t. 4751 (Hooker, 1853),

Plumeria lutea Ruiz & Pav. t. 5779 (Hooker, 1869);

Plumeria filifolia Griseb. t. 936 (Tiernan et al., 2020)